- Home

- Sven Carlsson

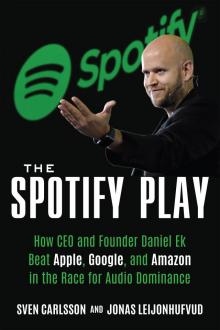

The Spotify Play Page 9

The Spotify Play Read online

Page 9

Within a few months, the mobile team had built an app that met Daniel’s specifications. Gustav had flown to London with Niklas Ivarsson to negotiate with Sony and Universal. Daniel had been right; the app was approved without too many questions. After all, a strong premium service meant more revenue for the music industry, and higher personal bonuses for its executives.

In July 2009, Daniel stepped into Soho House on Greek Street in London, a dimly lit members’ club full of designer furniture. He approached a familiar journalist named Rory Cellan-Jones, who was a tech correspondent for the BBC.

“I have something to show you,” the Swedish CEO said, with a wry smile and an iPhone in his hand.

Rory Cellan-Jones was used to getting daily news tips from startups, but Daniel’s pitch was special. It was the hot Spotify music client, inside an iPhone. The app was still in beta and would crash occasionally, but it carried several impressive features. For one, you could download your playlists to the phone and listen to them on the subway, where the 3G signal was crap.

The BBC journalist tried the app over the course of a few days, concluding that it would prove the Swedish’s company’s big breakthrough. Soon, he had broken the news of Spotify’s forthcoming mobile product.

Toward the end of July, Gustav’s team submitted the app to Apple’s App Store. Many staffers were afraid that Apple would find an excuse to block it. After all, they were asking Steve Jobs to open the door to a competitor.

Ticket to Ride

In early 2009, Spotify resumed negotiations to launch in the United States. Fred Davis and his team were gradually becoming less involved, with Daniel Ek relying more on Ken Parks, Petra Hansson, and Niklas Ivarsson.

Late in the summer of 2009, Daniel received a long email that gave him renewed hope. It came from Napster’s co-founder Sean Parker, who had made a killing off of his shares in Facebook and would soon become a billionaire.

“You’ve built an amazing experience,” Sean wrote. “Ever since Napster I’ve dreamt of building a product similar to Spotify.”

Daniel could hardly believe his eyes.

Sean Parker had moved on from Napster, becoming Facebook’s first president at the age of twenty-four. But in 2005, police found cocaine in a vacation home he was renting. He wasn’t charged, but the arrest rattled investors and led to his resigning from Facebook. Now, Spotify had become his new obsession.

Sean had recently met Daniel’s personal envoy, Shakil Khan, at a private barbecue in New York City. The American had asked about the music coming out of the speakers. It turned out that Shak could offer him a private demo of a service that had yet to be launched in the US. Shak gave Sean one of Daniel Ek’s secret, prepaid invites.

In his email, Sean waxed lyrical about the service, which he felt was completely superior to iTunes.

“You’ve distilled the product down to its core essence,” he wrote, before he opened the door to Facebook’s founder and CEO.

“Zuck and I have been talking about what this partnership should look like,” he wrote.

To Daniel, the email was a gift from above. At the very least, it could help his company launch and grow in the US.

Pick Up the Phone

During the spring and summer of 2009, the global economy was suffering. Just a few months earlier, America’s new president, Barack Obama, had pushed through a gigantic stimulus package, but the markets were still reeling from the financial crisis as Spotify started preparing its next round of funding.

The music service was adding tens of thousands of users daily, but the business itself was very risky. Spotify was paying more for its music than it was pulling in revenues, the company still had no US licenses, and the app had not yet been included in the App Store.

Daniel Ek now had seventy-five employees on his payroll. The finance team had been told to fetch a valuation of $250 million, a level that few investors found reasonable. Once again, Spotify had to raise capital based on an optimistic projection of their future growth. Their pitch centered around the famous hockey-stick graph, the idea that the company’s modest growth would shoot up once they had more money to hire staff, enter new markets, and keep growing.

Several high-profile US funds passed on the deal, but the finance team—led by the CFO, Daniel Ekberger—found a willing trio of investors from Europe and Asia. The group consisted of London’s Wellington Partners, German investor Klaus Hommels’s firm Lakestar, and Li Ka-shing, one of Asia’s top business magnates. Together, they invested around $25 million in a deal that valued Spotify at $270 million.

One summer night, Daniel Ek was awakened by a loud buzz in Vasastan in Stockholm. He grabbed his phone and tried to make out the number on the display. It appeared to be a call from Asia.

“Our chairman would like to speak with you,” a voice said at the other end, as Daniel would recall.

“Yes, okay,” the Spotify CEO said.

The chairman in question was the eighty-one-year-old Li Ka-shing himself. He was on Spotify, struggling to find his favorite song. Daniel Ek had to perform customer service duties over the phone to please his new investor.

The Times They Are A-Changin’

Soon, the financial press reported on Spotify’s new valuation and a user total of two million. The label bosses followed the progress closely. At the same time, many artists were skeptical of the streaming service, some even refusing to take part. Music by Metallica, Pink Floyd, and The Beatles was notably lacking in Spotify’s otherwise steadily growing catalogue.

In early August, a tall, slender man entered the Sony Music offices on Derry Street in London. It was Bob Dylan’s legendary manager, Jeff Rosen, who had come to learn more about this new European streaming service. His job was to ensure that his client was getting a fair share of the company’s revenues.

Jeff Rosen was an astute businessman. He had masterminded Bob Dylan’s Biograph, one of the record industry’s first CD box collections from the mid-1980s. Later, he convinced artists like Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, and Sinéad O’Connor to perform at a tribute concert for Bob Dylan in Madison Square Garden. The concert was broadcast live on pay-per-view, and was later released as a double disk DVD. In short, Rosen had made a ton of money for Columbia Records, which was now owned by Sony, and he demanded to be treated accordingly.

After the usual introductions, he ended up in a meeting room with glass walls and thick drapes, across from three mid-level managers at Sony’s digital division.

“So, tell me about Spotify,” Rosen said.

The heads turned to the only Swede in the room, Samuel Arvidsson, who did his best to describe how the service worked on a technical level. He explained the difference between Spotify’s free tier and its premium subscription service. He said that the record companies were paid a share of this revenue that they would then use to compensate artists. After a few minutes, Rosen cut in.

“How many shares in Spotify does Bob Dylan own?”

The room fell silent. The three label managers glanced nervously at each other. A widely quoted Swedish newspaper article had recently reported that the record companies, in secret, had been allowed to buy shares amounting to 17 percent of the company for next to nothing.

“Sony owns shares in Spotify, right? Now I’d like to know how many of those belong to my client,” Rosen said, as Arvidsson would recall.

The Sony Music trio knew that their label owned shares in Spotify, and they strongly suspected that Bob Dylan wasn’t entitled to a single one of them. But they promised to make inquiries. According to one account, one of the managers sent an email to Thomas Hesse, Sony’s Chief Strategic Officer in New York. He would not recall receiving a clear answer.

A few days later, Bob Dylan withdrew all of his music from Spotify. The news sent a wave of fear through Spotify’s office on Humlegårdsgatan. Having a legendary singer-songwriter like Bob Dylan leave the service was bad enough. But what would happen if Bob Dylan got Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder

, Sinéad O’Connor, and all his other buddies to do the same? If enough big names boycotted Spotify, the service could quickly become irrelevant.

Fula Gubbar

The press broke the story of Bob Dylan’s boycott in mid-August 2009. Reporters at the Swedish tabloid Expressen made calls and reported that several other musicians were considering the same move. The well-known Swedish pop star Magnus Uggla, signed to the same label as Bob Dylan, wondered aloud why Sony Music would be allowed to buy several percent of Spotify for the paltry sum of a few thousand dollars.

“It’s because Sony has sold out their artists,” Magnus Uggla wrote on his blog before launching into a colorful attack on his own label and its Swedish managing director, Hasse Breitholtz.

“One thing is certain. I’d rather be raped by The Pirate Bay than fucked in the ass by Hasse Breitholtz and Sony Music. I will therefore remove all my tracks from Spotify and wait for an honest internet service,” the artist declared.

The reporters at Expressen tried to reach Spotify for comment, to no avail. They then paid a visit to Spotify’s office on Humlegårdsgatan, where they were denied entrance. Finally, Spotify’s press people sent out a short statement where Daniel Ek described his company as “a significant digital revenue source” for the industry. The reporters also reached Hasse Breitholtz at Sony Music.

“Both Spotify and the record companies pay royalties to the authors—Pirate Bay pays nothing,” the label head was quoted as saying.

The tabloid reporters also reached out to Per Sundin at Universal Music. They asked how much artists were paid each time someone streamed a song. It was a straightforward question. But Spotify’s secret deals with the record companies were so complicated that it was impossible to answer in kind. Therefore, Sundin couldn’t offer a clear explanation.

This chain of events would repeat itself many times over the coming years. An artist would make a public statement about Spotify ripping off creators, and Daniel would react by stating how much Spotify was paying the industry as a whole. But neither Spotify nor the record companies would go further than that. One reason was that Spotify’s revenue sharing agreements with the industry, while pegged at around 70 percent, would fluctuate wildly depending on a variety of variables. Another was that the labels had their own agreements with artists that they wouldn’t discuss in public. There wasn’t a neat figure to sum up the payout for every stream.

The artists had many legitimate reasons to complain. In 2009, Spotify’s payouts were still relatively small—and would continue to be as long as the overwhelming majority used the free version. The artists could argue that Spotify was growing at their expense, while the record labels had a vested interest in the success of the service. After all, they owned shares. Another complicating factor was that streaming services had a much longer payout cycle. Customers paid for CDs and downloads upfront, while streaming revenues trickled in gradually over many years.

Certain artists now started demanding that their music only be available to Spotify’s paid subscribers, but Daniel refused. He made it clear to the record companies, and to his staff, that every artist would join Spotify on the same terms. The full catalogue had to be available both to free users and paying subscribers. Otherwise the whole business model would fall apart.

While the commercial launch had made Spotify’s communications more open, the spat with Bob Dylan made the company pull back. One former employee would recall how, around this time, Spotify’s head of marketing, Sophia Bendz, began to demand that they conduct themselves more like an American tech giant. The company would communicate on its own terms when it had something to say, and make few comments beyond that.

Over the years, Spotify’s founders would often feel that they were misunderstood and mistreated by the media and the outside world. Martin Lorentzon generally felt that journalists were out to get him and often got the facts wrong. Daniel—known to buy thick stacks of magazines before boarding a flight—appreciated a good read, but saw much of the coverage of Spotify as sloppy. He would try to limit his appearances to reputable news outlets where he could deliver strategic talking points.

As a result, Spotify adopted an “us against the world” culture. The employees were told not to speak to the media without explicit approval. Among journalists, Spotify would become known as an exceptionally opaque company. At parties and gatherings, Spotify employees would clam up at the mere mention of a journalist being in the room.

In the months after Bob Dylan’s defection, Daniel and his team carefully examined Spotify’s user data. The boycott didn’t affect the figures to any great extent. Users did not appear to abandon the service, and new ones continued to join at an undiminished rate. Nor was there a major string of boycotts from other artists following the singer-songwriter’s lead.

Many famous artists would abandon Spotify over the years, but the record companies would generally succeed in luring them back. As much as they disliked the business model, abstaining from the service didn’t do them much good either. Their CD and download sales largely did not increase when they left Spotify; they just missed out on a revenue stream that was growing in importance. Bob Dylan was no exception. Less than three years later, his music was back on Spotify.

Whether artists would share any of the profits from Spotify shares, however, would remain hotly debated for many years to come. It would resurface with a vengeance ahead of Spotify’s IPO, nine years after Bob Dylan’s original boycott.

I Gotta Feeling

In late August 2009, a few dozen Spotify employees met up by Nybrokajen, a small dock lined by boats in central Stockholm. They boarded small recreational motorboats and headed out for an evening in the archipelago. Martin Lorentzon, who loves Swedish traditions, was laughing in the back of one of the boats and fiddling with his phone.

“What do you think, is Apple going to let us into that goddamn App Store?” he said, grinning. “Who wants to bet a thousand crowns?”

They anchored the boats in an inlet called Skurusundet. The coworkers unloaded picnic food, beer, sausages, and disposable grills and held a simple barbecue together by the water in the evening sunshine.

When the sun finally started setting, they returned to the city for a night on the town. They anchored their boats in the canal by Djurgården and made their way to Utecompagniet, an open-air restaurant on the Stureplan square. Martin ordered drinks and champagne and suddenly, made an announcement.

“We got it!” he shouted.

The Spotify employees exploded with joy and started toasting and congratulating each other. The drinks kept coming and emotions ran high.

The evening is said to have ended abruptly after one employee emptied a champagne bucket of ice water over Martin’s head. The Spotify co-founder lost his temper. The employees finished their drinks and parted ways.

For the rest of the world, the news became official on August 27. Daniel Ek confirmed it in a tweet.

“We’re happy but have had a great dialogue with Apple all the way. They’ve been great!” he wrote.

Behind the scenes, the atmosphere between the two companies had been less than perfect. For years, Spotify would have a hard time getting new versions of their app approved by the App Store. The developers would often complain about how Apple was making things more difficult by changing or reinterpreting their own guidelines.

The conflict over Apple’s outsized power over the app economy had only begun.

Bridge to America

SPOTIFY’S BUSINESS MODEL RELIED ON volume. In order to succeed, Daniel Ek had to outgrow his competitors, enter the US market, and become one of the world’s biggest music-streaming providers. If investors didn’t see constant breakneck growth, they would stop pumping in the cash that fueled the company and Spotify would likely spiral to its death. Daniel knew it, the heads of the record companies knew it, and Steve Jobs knew it, too.

The Apple CEO had seen enough streaming companies fail and falter to understand t

he importance of momentum. Apple had allowed Spotify to be part of the App Store and keep growing in Europe. But, when its founder heard that Daniel was looking for music licenses in the US, he pushed back, as several people would recall.

Some saw Jobs’s behavior as a whisper campaign intended to stop, or at least delay, Spotify’s entry in the US. Apple’s chief executive had, after all, spent years building and marketing iTunes together with his allies at the major labels. It had become the world’s largest music store, and an integral part of Apple’s ecosystem, driving the sale of Macs, iPods, and iPhones. Spotify was like a foreign vermin threatening to invade Apple’s walled garden.

Many music executives shared Jobs’s perspective. Sure, Apple was dominant, but the company was selling downloads for billions of dollars, giving around 70 percent back to the industry. Spotify’s growth was based on giving music away for pennies on the dollar, with a vague promise of changing digital distribution down the line.

If Daniel wanted the keys to their market, he needed to make them an offer they couldn’t refuse.

California Dreamin’

On a sunny day in September 2009, one of America’s best-known tech journalists stepped into Centre Point in London. The sound of her heels hitting the marble floors echoed through the lobby. Kara Swisher had covered the industry for more than ten years, interviewing names like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. Today, she had an appointment to see Daniel Ek.

Swisher took the elevator up to Spotify’s offices, set up her video camera, and opened the interview with a bit of flattery.

“You’re it in Silicon Valley,” she said, as the camera started recording.

Daniel smiled cautiously.

“We’re quite big here in London,” he said. “Hopefully we can make our leap over to the US quite soon.”

He then launched into his usual pitch: Spotify was going to beat the pirates and save the music industry. When asked about the company’s future direction, he was clear.

The Spotify Play

The Spotify Play