- Home

- Sven Carlsson

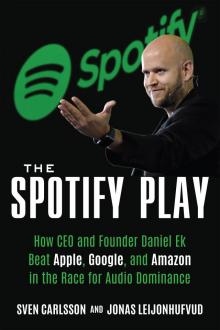

The Spotify Play

The Spotify Play Read online

Copyright 2021 © by Sven Carlsson and Jonas Leijonhufvud

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For more information, email [email protected]

Diversion Books

A division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

www.diversionbooks.com

First Diversion Books edition, January 2021

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-63576-744-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-63576-745-2

Printed in The United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress cataloging-in-publication data is available on file

Contents

Prologue

1. A Secret Idea

2. The Engineers

3. Rågsved

4. Party Like It’s 1999

5. Better Than Piracy

6. “Wealth-type Money”

7. All Music for Free

8. Bridge to America

9. “Schmuck Insurance”

10. Sean & Zuck

11. “Winter is Coming”

12. Spotify TV

13. Apple Buys Beats

14. Death Valley

15. From Nashville to Brooklyn

16. Big Data

17. Brilliant Sweden

18. The Streaming Wars

19. Wall Street

20. The House That Daniel Built

Acknowledgments

References and Sources

About the Authors

Prologue

Toward the end of 2010, Spotify had spent two years amassing seven million users in Europe. But the company’s crucial US launch faced massive delays. Founder and CEO Daniel Ek was struggling to understand why.

“He called and breathed down the line,” he told one of his staff members, who would later recount the conversation.

“Who?” the colleague said.

“Steve Jobs,” Daniel replied.

Daniel’s colleague wondered if his boss was serious. “What do you mean? He didn’t say anything? How do you know it’s him?”

“I know that it was him,” Daniel said.

After years of frustrating negotiations with the major record labels, Spotify’s founder was beginning to understand who truly called the shots in the music industry. Apple’s resistance to Daniel’s free music streaming was becoming clear, and it was starting to burden him. The industry power dynamics at play weighed heavily on his mind as he walked to Spotify’s headquarters in Stockholm, and on his many flights to New York, London, and Los Angeles.

The long shadow of Steve Jobs had towered over Spotify since the startup was founded in 2006. At that point, Apple was already the world’s largest platform for digital music distribution, with iTunes and the iPod music player working hand in glove. Now, seven years after the launch of the iTunes store, Apple’s grip was even firmer.

While Daniel Ek was fretting over iTunes in Stockholm, Steve Jobs was in Cupertino, California, obsessing over his own arch rival. The iPhone had become a huge success after launching in 2007. But three years later, his iconic product was under siege from a growing fleet of Android smartphones powered by Google. To Steve Jobs, music was a crucial weapon in a “holy war” against the search giant and its operating system.

The iTunes model, based on downloads for 99 cents per song, worked on any Apple device, and on PCs. But Android phones were not part of the iTunes ecosystem, and Steve Jobs liked it that way. He had spent years building Apple’s lucrative walled garden.

And he would be damned if one of his key competitive advantages—easily accessible music—was compromised by some upstart from Europe streaming music for pennies on the dollar.

In this context, Spotify was a threat. The Swedish service was catching on in several European countries, and had created a lot of buzz in the US. Spotify had the potential to become a major challenger on Apple’s home turf. What if the startup was acquired by Microsoft or, even worse, Google?

For Daniel, access to the US was a matter of survival. After more than four years of growth and constant label negotiations, he was so close to being the world’s largest music market that he could almost taste it. By now, the 27-year-old Swede had powerful allies in the music industry. He had earned the support of Sean Parker, Napster’s outspoken co-founder, and he was on a first-name basis with Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who had promised to help Spotify with their launch. Daniel had even lined up a deal with Universal Music, the label with the closest personal ties to Steve Jobs. But suddenly, Universal’s executives refused to sign. The machine ground to a halt, and Spotify’s investors were becoming nervous. In fact, Spotify would soon start to see negative user growth for the first time. It could all come crashing down.

Perhaps Daniel’s only option was to talk directly with Steve Jobs. According to several sources, however, the Spotify CEO never got to meet his counterpart in Cupertino.

Despite his failing health, Steve Jobs continued to fight for his vision. He aimed to shift iTunes over to the cloud, and he wasn’t afraid to badmouth Spotify and ad-funded music streaming to any label executive who would listen. As this book will show, many of them did.

At Spotify’s headquarters, the air was thick with tension in late 2010. Their launch in the US kept meeting delays that nobody could explain. The company’s top brass whispered about the bosses at Apple, Universal, Warner, and Sony. But only a few select people had any firm details.

Daniel’s colleague would never find out if it really was Steve Jobs who made that fateful phone call. The Spotify CEO was, after all, known to sometimes tell stories that were hard to verify.

WHAT HAPPENED IN the following years now belongs to history. Since launching in Sweden in 2008, Spotify can rightfully claim to have saved the record labels from piracy, returned the music industry to growth, and forced Apple—a tech industry behemoth—to change its business model.

While Steve Jobs broke the album down into tracks and playlists, Daniel Ek popularized the freemium subscription model, and laid the groundwork for a new era of playlist by algorithm.

With a market cap in the tens of billions on Wall Street, Spotify is the largest music streaming company in the world, with more than fifty million songs, over a million podcasts, business in more than ninety countries, and a user base expected to surpass 350 million in 2021. Nearly half of its users now pay for the ad-free version, making the platform the industry’s most important source of revenue, with billions of dollars delivered every year. But what really happened during the company’s spectacular journey to the top?

The Spotify Play is an unofficial corporate biography detailing how a secretive startup from the Stockholm suburb of Rågsved revolutionized music distribution.

As Swedish business journalists, the two of us have met and interviewed Daniel Ek and his co-founder, Martin Lorentzon, several times over the years. They have, however, declined to partake in any exclusive interviews for this book.

But in August 2018, as we were writing the Swedish edition of The Spotify Play, we were among the journalists invited to Spotify’s new, state-of-the-art headquarters in Stockholm. During a brief question-and-answer session, we asked Daniel Ek to name the single most important reason for his company’s success.

“I’ll give you two reasons,” he replied. “First of all, we were committed to the freemium business model when no one else was. This was very controversial.

“Second, we started in Sweden, proved our model, opened up in more European count

ries, and grew organically one country at a time. That’s what finally made the music industry realize that our model was the future.”

Daniel Ek has been reluctant to tell the full Spotify story. He has talked about certain aspects in the press, while carefully guarding the rest. So, to put this book together, we interviewed more than eighty sources—some on the record, some on background—who have been along for the journey. Many of those we asked declined out of a sense of allegiance. Others felt compelled to contribute, despite their loyalties. Some of our interviewees have served as executives at Spotify. Others have been board members, investors, or music industry decision makers. A few are direct competitors.

We have also relied on mountains of documents—some public, such as annual reports, and some confidential. We have pored over the interviews and public appearances that many other Spotify employees have made over the years.

The Spotify Play is a story of how strong convictions, unrelenting will, and big dreams can help small players take on tech titans and change an industry forever.

Sven Carlsson and Jonas Leijonhufvud

Fåglarö, Stockholm

August 2020

A Secret Idea

In the fall of 2005, Daniel Ek passed through Vasastan in central Stockholm. His thoughts were brimming with an idea for a new company. He had a plan and a potential partner, but the timing still wasn’t right. What he needed right now was a job and an income.

The past few years had taken their toll on him. He had been working full-time since he graduated from high school. His was a world where new ideas sprung up all the time, and the work never really stopped. Daniel’s hustle included formal roles at tech companies, where he would get paid to apply his skills in online advertising and search-engine optimization, but he was also constantly developing other ideas, putting small teams to work on projects that he would often fund himself.

It was a taxing lifestyle. His hair was thinning, his clothes were unkempt, and he looked older than his twenty-two years. But none of that mattered much to him. He was a man with big ideas, and a mind fixated firmly on the future.

Daniel walked down Tegnérgatan until he arrived at the site of his job interview, a pub called Man in the Moon. It was furnished in a British style, with dark wood paneling lining the walls and sofas covered in green leather upholstery. After a moment, he fixed his gaze on a bespectacled man in his late thirties who waved him forward.

Mattias Miksche was dressed like your average tech entrepreneur—t-shirt and suit jacket. He had just become CEO of Stardoll, a website full of virtual paper dolls that catered to young girls. Stardoll had new investors, and the site’s user growth was impressive. Now, Miksche needed to recruit staff, rebuild the back end, and scale up the company for the international market.

The two shook hands and sat down. At first, the low-key Daniel Ek didn’t make much of an impression. But as the conversation unfolded, Mattias Miksche felt the young man growing in confidence. The disheveled twenty-two-year-old offered a variety of interesting thoughts on where the industry was heading.

“I’d like you to be our new CTO,” Mattias Miksche said, at last.

Daniel was ready and willing, but he wanted to join only as a consultant, not as a full-time employee.

“I have another thing that I’ll need to take care of,” he explained.

Mattias Miksche accepted, and the meeting ended with a handshake.

Light My Fire

To manifest his secret idea, Daniel Ek knew he needed a partner. He had recently met Martin Lorentzon, a thirty-six-year-old entrepreneur with a crooked grin and slicked-back hair. Lorentzon had moved to Stockholm from the textile city of Borås near Sweden’s west coast in the late nineties, and elbowed his way through the capital’s resurging tech scene. And if everything went as planned, he would soon be a very wealthy man.

When the tech bubble burst in March 2000, things had turned sour for nearly the entire industry. Martin, however, had been lucky enough to build a company in one of the few corners of the sector that survived the crash and thrived in the years that followed. With his partner Felix Hagnö, he had founded an affiliate marketing company called Tradedoubler, which offered a partially automated system for banner placement, in which advertisers paid for results rather than exposure. The company had taken off since its inception in 1999 and was now—near the end of 2005—poised for an initial public offering on the Stockholm Stock Exchange.

When the two first met, Daniel was only three years out of high school, but he already had a good deal of experience in Sweden’s fledgling online advertising business. In a recent side project, he had gathered a few programmers to create a new service he called Advertigo. The system was said to know what advertisement best fit a given space online. Advertisers could opt to pay only when the ad generated the phone number of a potential customer.

With the economy rebounding, Daniel was seeking new opportunities, which led him to Tradedoubler’s head office on Norra Bantorget in Stockholm, and into Martin’s orbit.

The pair first met in summer 2005, when Daniel tried to pitch Tradedoubler on a product search engine akin to Google’s “Froogle” (later redubbed Google Product Search). According to his own retelling, Martin wasn’t very impressed, but the two of them stayed in touch. Not long after, Daniel organized a game of Counter-Strike between his employer, the search-engine optimization firm Jajja, and Tradedoubler. Daniel’s team won the challenge handily, making a strong impression on Martin. Years later, he found out that Daniel had secretly enlisted the help of several professional gamers from the renowned Swedish Counter-Strike team Ninjas in Pyjamas in order to win.

Martin had no formal title at Tradedoubler. Instead, he took the role of an omnipresent founder, boosting the morale of his employees and troubleshooting various challenges. One former colleague would later describe him as the company’s “flying goalkeeper,” using a metaphor from two of Sweden’s favorite pastime sports: soccer and ice hockey. Martin had a brash, competitive spirit about him. Unwilling to be pinned down by specific responsibilities, he was ready to assist as negotiator, salesperson, problem solver, and cheerleader. Now, in the fall of 2005, his main goal was to take Tradedoubler public. After nearly seven years with the company, he was ready to sell off his shares and move on to something new.

Despite an age difference of almost fourteen years, Daniel and Martin hit it off. They found common ground discussing search engines, metadata, and how to generate large amounts of online traffic to sell advertising. More importantly, they bonded over the potential of peer-to-peer technology, in which files are distributed directly between users’ own hard drives without needing to transfer through a central server.

The soon-to-be partners also had several friends in common. One was Jacob de Geer, a social acquaintance of Daniel and one of Tradedoubler’s first employees. Much later, Jacob de Geer would make hundreds of millions of dollars by selling his payments company, iZettle, to PayPal.

In the fall, Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon began meeting regularly to discuss business ideas. Slowly, Daniel opened up about how he wanted to merge peer-to-peer technology with commercial content. Martin liked what he heard and seemed eager to give it a shot. But first, he had to list his company and sell off a large portion of his shares.

True Colors

A month or so after his job interview in Vasastan, Daniel Ek started to work as chief technology officer (CTO) at Stardoll. He quickly recruited several programmers out of his own network, and the team started to rebuild the website from scratch.

Colleagues found Daniel to be an introvert who avoided conflicts. He never wore a button-down shirt, preferring instead jeans and yesterday’s t-shirt. He’d often forget to clean up after himself. Once, allegedly, a sign proclaiming that “Daniel Ek’s mom doesn’t work here” appeared in the office kitchen. Soon, it disappeared, without any mention from Daniel.

After a few weeks, however, the twenty-two-year-old’s cowor

kers began to see how gifted he was. Mattias Miksche delighted at Daniel’s progression and at his own recruitment of the new CTO. As the weeks wore on, Daniel ensured that traffic to the website was through the roof. And when his shyness gave way, he could be both funny and fascinating.

Stardoll.com became one of the internet’s biggest playgrounds for girls between the ages of ten and seventeen. The website suddenly had millions of weekly users and was raking in cash by selling virtual clothing and accessories. Mattias Miksche now ran one of the hottest startups in Stockholm. He started recruiting the best engineering students in town, fresh out of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, widely recognized as the MIT of Sweden. He also secured $10 million in financing from two of the world’s leading venture capital firms: Index Ventures in London and Sequoia Capital in Silicon Valley.

Despite this success, Daniel was committed to leaving Stardoll as soon as he could. His head and heart were in getting his own company on its feet. He also considered taking some of his colleagues with him on his new adventure. One candidate was a twenty-seven-year-old development director named Henrik Torstensson. Another was the company’s artistic director, Christian Wilsson, a tall and lanky guy with a dry sense of humor. But above all, Daniel wanted to recruit Andreas Ehn, a phenomenal programmer with side-swept bangs who dressed in carefully ironed shirts. Andreas had attended the private prep school Tyska Skolan in Stockholm, spoke with a posh accent, and had a worldly air about him. He’d recently interned at the software company BEA Systems in Silicon Valley as a part of his final year at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology. He never completed his degree, opting instead to work at Stardoll. When Daniel opened up about his side project, the ambitious Andreas Ehn was more than a little curious.

Paradise City

On November 8, 2005, Tradedoubler was listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. Martin Lorentzon was now able to sell a large portion of his shares for nearly $12 million. Felix Hagnö, who owned approximately twice as much of the company, raked in even more.

The Spotify Play

The Spotify Play