- Home

- Sven Carlsson

The Spotify Play Page 4

The Spotify Play Read online

Page 4

While an avid musician, Daniel was a computer virtuoso. He received his first computer, an old Commodore VIC-20 which hooked up to the television, as a five-year-old. It would soon be replaced by a Commodore 64, complete with games that kept him occupied for hours every day. Early on, when he had trouble loading one of the games from the external tape deck, he asked his mother for help.

“You’ll have to solve that yourself,” she said, as Daniel would recall.

Eventually, Daniel’s stepdad gave him a PC. He started coding at the age of nine. By the age of eleven, he was imagining a career in technology and telling people that he was going to be “bigger than Bill Gates.”

Below the hill, a short walk from the family’s apartment, lay Rågsved’s city center. Next to it was the local youth center, with a facade covered in a renowned 1989 graffiti mural. It had a gym and rehearsal space, and local kids would play table tennis and floorball there. Daniel Ek was often seen there in his early teens. Micke Johansson, a staff member, would remember Daniel as a kind and well-behaved kid. He recalled how Daniel would often arrive on his own, and sometimes practice bass guitar.

Daniel was reserved, at least compared to his mother. Elisabet was more of a straight talker, one of few parents that really got involved in the youth club’s activities. Center manager Rickard “Ricky” Klemming, a man in his 60s, ran a tight ship and was fond of involving the local talent. When he needed to install computers with fast internet connections, he turned to Daniel, who had earned a reputation as a computer wiz. In a show of initiative and salesmanship, Daniel rose to the occasion and secured what he would describe as his first professional gig. He had overpromised, and needed the support of his stepdad to get the job done, but they managed to do it. It felt good. Daniel Ek was on his way to becoming Rågsved’s youngest IT consultant.

Staten och kapitalet

When Rågsved was built at the end of the 1950s, the suburb was considered a wonder of modernism, with its towering apartment blocks and a central building in the shape of a horseshoe. But just a decade later, the picture changed entirely. Rågsved was suddenly described as a “problem area” associated with drugs and alienated youth.

Toward the end of the 1970s, the Swedish punk band Ebba Grön put the area on the map. In just a few years, the band’s brooding lead singer, Joakim Thåström, became a national sensation. The band played to packed houses at Oasen, the local club next to the youth center.

Punk rockers from all over Stockholm came there to see Ebba Grön and suddenly Rågsved—or “Råggan,” as it was called—became the heart of the whole punk rock movement in Sweden. The music united a generation that wanted to rebel with the clamor of Ebba Grön’s politically charged hit “Staten och kapitalet” (“The State and the Capital”) as their anthem.

When the local politicians announced that Oasen was to be rebuilt, the punk rockers responded by occupying the building. They painted protest signs and barricaded themselves for ten days until they were dragged out by police.

When Daniel Ek was born, in February 1983, the local punk scene had all but died out. His generation would rally around another call to arms against authorities trying to silence their music. Instead of punk rock, they were captivated by file-sharing, a culture that was deemed illegal and would spawn its own political movement.

School Daze

In 1996, Daniel Ek started middle school in Rågsvedsskolan, a short walk from the youth center. It had already earned a reputation as a rowdy school. Former students would describe how some kids fought, took drugs, and drank on the weekends. But for most, Rågsvedsskolan felt fairly normal. Many were proud, both of their school, and of the area they grew up in.

Daniel was not one of the bad kids who boozed and fought after the youth center’s disco nights. He stood out as a clever and talented student with a wide range of interests. A former classmate would attest to his excelling during his guitar lessons. He would play lead roles in the school’s musicals, befriending both boys and girls. He was, however, even by his own account, somewhat precocious, eager to talk to his teachers and to adults in general. He was top of the class in computer studies, but didn’t put in more effort than he had to. Outside of school, his confidence grew as he helped classmates and acquaintances with computer problems that seemed difficult to them, but easy to him.

Word traveled quickly, and when locals needed homepages, they began to turn to Daniel. He would often retell how he started to build websites and make money at the age of fourteen. A few years later, he would teach HTML and programming to his classmates, turning them into teenage subcontractors. As his skills grew, Daniel started forming new friendships online, interacting on various chat forums. He would share hacker tips and exchange pirated files.

At one point, Daniel built his own virtual counter for his homepage. The counter would tally the number of visits to the homepage and show the number to each viewer. Soon, others on the Internet began to embed Daniel’s counter on their homepages, teaching him an early lesson in online virality.

“I began to understand that, hang on a minute, it’s all connected,” he would explain. “If something is good, it will spread on its own.”

Daniel graduated from middle school in June of 1999, with top grades in English, music, history, the history of religion, social studies, and computer studies. His strong report card got him admitted to IT-Gymnasiet, a technical high school in the suburb of Sundbyberg, across the city.

Breaking the Law

That August, Daniel Ek began to commute to high school. Every morning he would take the green subway line to T-Centralen, the node of Stockholm’s metro system in the middle of the city. Then he would switch to the blue line toward Hjulsta. Sweden was in the middle of an internet boom and the hallways of his new school were full of optimism. Every student was provided with their own personal computer, which was practically unheard of at the time. They were inspired to dream big and filled with the promise of lucrative careers in IT.

“All we did was toss ideas around. We were thinking that we were going to be the world’s greatest,” as Daniel would describe it.

During his first year of high school, Napster had just launched. Suddenly, Daniel could download all the world’s music for free. For a music-loving hacker in his teens, it was almost a religious experience.

“Napster is probably the internet service which has changed my life more than anything else,” he would say.

For Daniel, and many in his generation, file-sharing was a way of life. At school, Daniel and his classmates started broadening their tastes and listening to a greater range of music than when they bought CDs. Young people would no longer wrap their entire identity around a single genre of music. The influence of Napster‚ and the countless services that followed, was profound.

Later, when piracy came under fire, Daniel’s generation banded together and demonstrated for the right to file-share without fear of prosecution. Daniel never ended up on the barricades. Instead, he would try to make peace between the pirates and the music industry. And he would get Sean Parker, one of Napster’s two founders, to join him.

School’s Out

At school, Daniel Ek and his fellow students were taught how to program in C++ and build homepages using software such as Dreamweaver. Some of their classes took place in Kista, a high-tech office park north of Stockholm, where both Ericsson and IBM had offices. There, the students learned to disassemble and reassemble computers.

Daniel’s ambitions already stretched far beyond what he was learning in class. At the age of sixteen, he sent a job application to Google. The search engine, started by Stanford students Larry Page and Sergey Brin, had only been around for about a year. A representative from Google wrote back to thank him for his interest and encouraged him to get back to them when he had a college degree. Irked by the setback, Daniel eventually tried to build his own search engine. He invested his own money in the project, which turned out to be more difficult than expected.

Eventually, when he published the source code online, thousands of developers started contributing to it. The product lived on for many years and would eventually receive attention from companies such as Yahoo!.

In high school, Daniel matured into a young man. In the school’s annual photo catalogue, Sweden’s version of the yearbook, his blond bob cut had been replaced by dark bangs, combed casually to the side.

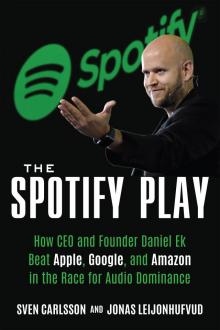

Daniel Ek, 16 years old, at his high school, IT-Gymnasiet, in Sundbyberg, a suburb of Stockholm. (Jonas Leijonhufvud)

When school was over, Daniel and his classmates would stick around and toy with their computers, using the school’s LAN connection to play the computer game Half-Life and a subsequent version called Counter-Strike.

Former classmates would describe Daniel as shy around the school’s few female students. He would avoid their gaze in the hallways but come alive when he interacted using the popular chat program ICQ. His online persona was confident and charming, but he wasn’t known to have landed many dates, something Daniel himself would later attest to. He did, however, find that learning to play “Iris,” a heartbreak anthem by the Goo Goo Dolls, on his guitar eventually charmed some of the girls around him.

Several former classmates would describe Daniel as ambitious, smart, and imaginative. He was also one of a select few students who had consultancy gigs on the side. During his last year at school, he worked almost full-time on various projects, fueled by a diet of Red Bull and coffee. He worked for a hot internet consultancy firm called Spray, and would guest star as acting CTO at Tradera, an auction website that would later be acquired by eBay, helping them improve their search engine optimization. He even hooked up some of his classmates with paid work, building websites and doing customer service. Some would suspect that Daniel took a far higher cut from some of these gigs than they did.

While in school, Daniel Ek began to realize that he was never going to be the best coder, even among his peers, as he would later recall in interviews. But he clearly had a knack for coming up with new ideas, motivating people, and getting stuff done.

In his final year, Daniel often cut class in favor of his entrepreneurial gigs and side projects. His grades suffered and he irritated many of his classmates by missing group assignments and giving perplexing excuses. One former student would describe how Daniel claimed that he was due to go on tour with some well-known band, something the classmate wrote off as nonsense.

His tendency to employ wishful thinking made some students doubt Daniel’s intentions. Behind his back, some of them would refer to him as “Mytoman-Danne,” or “Lying Danny,” in English.

“What’s Lying Danny cooked up now?” one former student would recall the teenagers at school saying.

Few could recall specific examples, but Daniel would often engage his friends with talk of business ventures, money, and musical feats that seemed fanciful. He wasn’t exactly braggadocious, another source said, he just seemed to get caught up in the moment somehow.

These early accounts of Daniel Ek’s entrepreneurial hustle stand out as an unvarnished, schoolyard version of traits that would follow him going forward. Speaking off the record, people close to him would, in later years, often describe Daniel as a determined ideas man who would sometimes embellish and distort the present reality so that he could instill belief in his vision. The trait is not uncommon among entrepreneurs in the tech sector. These descriptions bear a certain resemblance to the “reality distortion field” attributed to Daniel’s future rival Steve Jobs, who would employ a blend of charisma, hyperbole, and conviction to inspire himself and others to believe in ideas that, when considered rationally, defied reality.

Just like Jobs, Daniel would eventually get away with skirting the facts while selling people on a grander vision. As a high school student, though, he was still finding his voice. Sometimes his enthusiasm got the best of him, and his friends and schoolmates pushed back.

“It’s like he had clear visions inside him that came out as words before they actually happened,” one of his former peers would explain.

Daniel would recall that his last year of high school was rough. He devoted his final few months to retaking tests and working to save his grades. By the time he graduated in 2002, the job market had cooled considerably. For the next few years, he would divide his time between working at tech companies and developing his own projects. He’d be on top of the world one moment, and tormented by self-doubt the next, uncertain of where he was headed.

Party Like It’s 1999

WHILE DANIEL EK WAS STILL living with his mother and downloading music in his boyhood bedroom, his future partner had already founded a company that would be worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

In April 1999, Martin Lorentzon had just turned thirty. He was a rising star on the Stockholm tech scene, sporting a cheeky smile, a fiery gaze, and thick brown, slicked-back hair. He had a mind full of ideas and a belly bursting with the kind of confidence that only newly printed money can bring. By day, he worked at one of the city’s leading venture capital firms, and by night he was an eligible bachelor about town.

Stockholm was now one of Europe’s hottest tech clusters. Internet consultancies with names like Icon Medialab and Framtidsfabriken (The Future Factory) went public and used their soaring stock to buy up competitors at a dizzying pace. In newspaper and television interviews, the founders of these companies were treated as emissaries from an exciting future that was said to be just around the corner.

In the posh restaurants and bars around the Stureplan square, the city’s new tech entrepreneurs would mix with fashion designers, film directors, pop stars, and captains of industry. The music business was experiencing its best year ever. The Cardigans were touring all over the world and Swedish producer Max Martin was working with superstars such as Britney Spears. Politicians, eager to take credit for the country’s cultural successes, would talk about “the Swedish music sensation.”

In London, the Swedish trio Ernst Malmsten, Kajsa Leander, and Patrik Hedelin added to the hype by raising $125 million with incredible speed to build Boo.com, an online fashion store for the international market. Upon launching in November 1999, Boo.com was immediately bogged down by technical problems. A few months later, when the dot-com bubble burst, it became one of the first spectacular bankruptcies. But in 1999, talk of a market crash was still theoretical. If anything, people with money to spare were anxious over the reverse outcome. They were scared to miss out on big returns.

One businessman who took a chance was Jan Stenbeck. He had spent the past decade using his family’s fortune, and his investment firm Kinnevik, to challenge old state monopolies with his telecoms firm, Tele2, and the broadcasting company MTG. In this new era, he was quick to start an online music store called CDON. He also invested in a web portal called Everyday.com, which for a brief period had Niklas Zennström as CEO.

The web portal failed, but Niklas Zennström would move on to join forces with Janus Friis and found Kazaa, a file-sharing platform that succeeded Napster, in 2001. Kazaa would become a worldwide sensation for a few years before being struck down by the record industry. Zennström and Friis’s greatest success, however, was Skype, which let its users make international calls for free, using only a computer connected to the internet. The company eventually turned Niklas Zennström into one of Sweden’s first tech billionaires. He would later invest some of his money in the online music sector, co-founding the music service Rdio. But that lay almost ten years into the future.

Before the turn of the millennium, Sweden’s premier industrial family, the Wallenbergs, also wanted in on the “new economy.” Their company, Investor, bet more than $100 million on the Swedish web portal Spray, which doubled as an internet consulting company. Spray would turn into a huge disappointment for the family and make the Wallenberg sphere wary of the Swedish tech sector for years to come.

Two Princes

In this whirlwind of technological optimism and fast money, Mart

in Lorentzon and Felix Hagnö were itching to start their own business. Both had moved to Stockholm from Gothenburg, Sweden’s second-largest city, on the west coast. They were relatively junior employees at the investment firm Cell Ventures, where they had been tasked with improving a neglected e-commerce platform. They spent most of their time at the office, located in one of the five identical high rises in the center of the Swedish capital. After regular hours, they would devise plans to build their own company, one that would automate the purchase and placement of internet ads.

Martin had what it took to sell investors on the idea. He was outgoing, creative, and energetic, bordering on hyperactive. He would turn on the charm when he needed to and if things got technical, he could lighten the mood with a lowbrow joke. Some found him a bit brash, but he wasn’t afraid to own the room, and that kind of behavior paid off handsomely in the bustling dot-com scene—even in Sweden, where bragging was frowned upon and most people avoided conflict. Felix was the sober yin to Martin’s impulsive yang. He came from a wealthy family that had started Joy, a chain of women’s clothing stores, in the 1970s. But Felix was more interested in computers than in fashion.

Martin Lorentzon had grown up in a suburban neighborhood in Borås, a textile town near Gothenburg. His mother was a teacher, his father an accountant. Both parents had been top-level athletes when they were young and Martin was sporty as well, with a strong competitive streak. As a teenager, he graduated from Sven Eriksonsgymnasiet in Borås with good grades. His school catalogue photo shows him looking like a young Patrick Swayze, with a blond-streaked mullet.

The Spotify Play

The Spotify Play